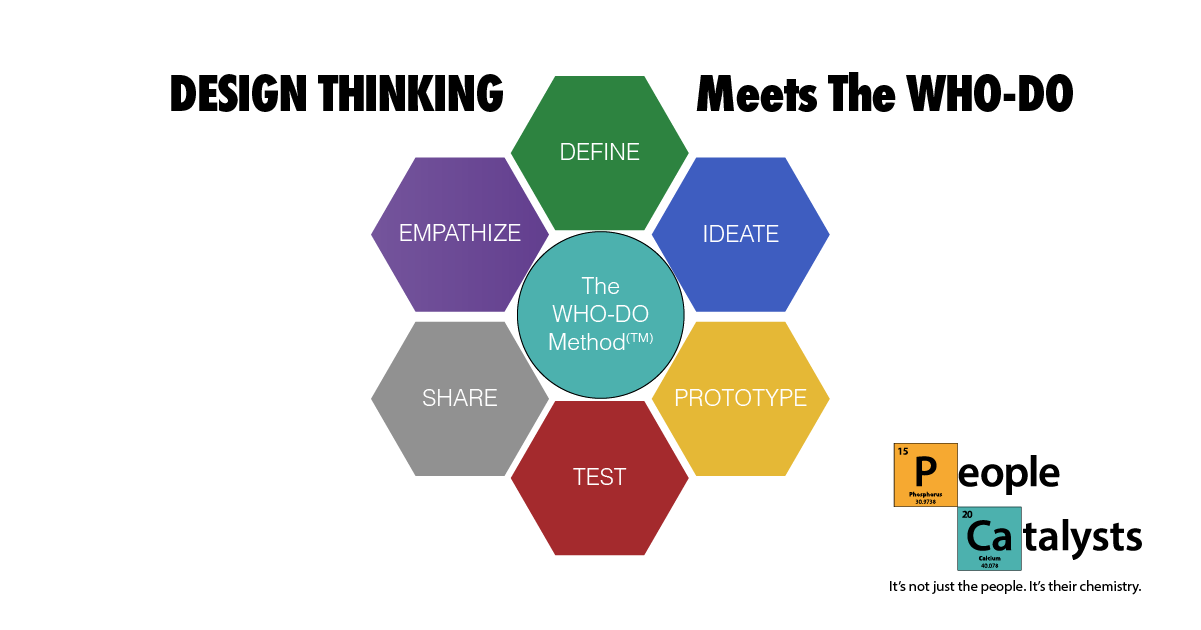

Design Thinking Meets The WHO-DO Method

Have you use Design Thinking within your organization? Do you want to increase it’s effectiveness by 300-800%? That’s what happens when you combine Design Thinking and The WHO-DO Method™. We don’t replace any great methodologies, we just add gasoline and a match to what it already being done.

Listen to the podcast here:

Design Thinking Meets The WHO-DO Method

Karla Nelson: And welcome to the People Catalysts Podcast, Allen Fahden!

Allen Fahden: Hello, Karla.

Karla Nelson: Hello good sir, how are you today?

Allen Fahden: Happy, happy, in a hotel room happy.

Karla Nelson: I swear, we’ve been in a lot of hotel rooms here recently. Thank goodness the WiFi is good.

Allen Fahden: The WiFi is good, and so is the echo, echo, echo, echo.

Karla Nelson: Well, I’m really excited about this podcast today, and we have just recently done a training with a lot of, you know, Fortune 500 companies, if not Fortune 100 companies, recently, and this kind of came out of all the preparatory work we did. And a lot of people know what design thinking is, and you have utilized it, and you’ve … for those of you that don’t, it’s a methodology to discover a problem and develop a solution.

And so, what we did is we overlaid design thinking with the WHO-DO method, so … because, you know, if you don’t overlay the two, and not get everybody at the right place, at the right time, doing the right thing, you’ll likely fall onto, you know, the previous podcast we did, the misfit’s wheel of misery, where-

Allen Fahden: Yes.

Karla Nelson: … you’re going to … I love that. You’re going to have disagreements, disappointment, because you’re not going to get the results, and then ultimately disengagement.

And then we’re also going to add on … we call it the five steps plus one of design thinking, because we’ve added a sixth step to that that we’ll talk about. And remember, with the WHO-DO method, it doesn’t replace anything, okay? It takes whatever you’re doing, and in this case we’re going to talk about it in conjunction with design thinking, and it puts gasoline and a match on it so that you can be three to eight times more effective. So, if you can be 300% more effective, obviously that’s moving the needle pretty heavily.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely. So with design thinking, it’s interesting, because that’s been around for about 15 years, and there’s really not much new to design thinking, because it was pretty much the way people did … built products, did marketing, and the steps are the steps. And the problem, of course, is that people will modify things when they get a hold of them, and so what happens is they usually eliminate steps, things like talking to the customer to see what the customer’s problem is.

And so one-

Karla Nelson: That’s so true. Don’t bother the customer.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, let’s just talk to ourselves. And so, when the design thinking regimen came in, one thing I think it really did that was good is it really broke it down into five steps, and you got to do all five steps. And the first two are so important that most people skip them, which is, you know, empathize with the customer to find the problem, and … However, you still need to have the right people doing it. So, you have the what and the how of design thinking, but you still need the who and the when.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, so let’s break this down then, Allen, what we’ll do … How about we go through the five steps, or like we call five plus one, the total six steps, because, again, like I said, we added that last one that’s really critical, and you already touched on it. That step one of design thinking is empathize.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, and so, in the empathize phase, obviously you go talk to your clients, your customers, and you find out, you know, what their problem is. And one of the questions we like to ask is, of course, what annoys you about the status quo.

But it’s also important who goes out and does this. And one of the things that we recommend, this is the overlay of the WHO-DO method, is that the shaker, that’s the idea person, should be taking the lead on this stage, which is empathizing, and that’s because shakers are wired to find creative solutions problem … to problems, and then they’ll take the ideas to the mover. And one of the things they are always looking for is these problems. Where’s a problem I can solve? Where’s a problem I can solve? Where’s one I can solve? Once they get that they’re very successful in this first empathizing piece.

But then it’s important to take these problems to the mover, and it’s important to be open minded, and not kill any ideas. And you know, even, you know, I suspect the problem is this, that’s an idea. So don’t kill that even, because sometimes that problem, in the right hands, usually a shaker showing it to a mover, that can make a great solution.

Karla Nelson: I love that, and when you talk about that piece, of the shakers, they’re so … they are so attracted to that. And in … we’re going to show you how you need everybody, just not at the same time, when you’re doing design thinking and utilizing The WHO-DO Method. Because the shaker is the person that walks around and can say, “That should be done. That should be done. You know, if somebody invented that …” So they’re really great at coming up with the beginning part about it, and they’re attracted to it, right?

And so, I always cringe when I hear, “Oh yeah, that’s a great idea. You should do that.” Because that’s hilarious to ask a shaker to do all … It’s just … It’s never going to work. They’re good at-

Allen Fahden: Never going to happen.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, never going to happen. And so, you can put that part of design thinking on steroids if everyone, then, is trained, right? So specifically in this stage, having the shakers understand the methodology, and to come up with a lot of ideas that they will then take to the mover, if not … the mover’s not shadowing them anyway, right?

So that brings us to the second stage of design thinking, which is define.

Allen Fahden: Yes, and just like the WHO-DO method, when the shakers bring a bunch of ideas to the mover, it’s the mover who sets the priorities. So, as we said, even the … what they suspect is the consumer’s problem, that’s an idea. So the mover, then, will set the priority on which problem is the first one to go after, not killing the others, as ideas, you don’t kill ideas, but which one, or set of problems, has the biggest impact.

And then the mover works with the shakers to clearly identify and lay out the program. So, that’s a really nice thing, because you get the idea people, who can conjure up the ideas, together with the person who can set the priorities and put things in order moving ahead.

Karla Nelson: Yes, exactly. And so … And really, defining the problem, we’ll talk about this in a minute, is you really want to identify the problem, not have a solution statement. And we’ll talk about that, because I want to keep on moving through these different stages here, because that’s something that happens really frequently. We’ll give you a good example of it as well.

And so, that brings us to the third stage of design thinking, which is ideate. So, that’s when you bring in the prover, you bring him into the mix. And you’ve identified the problems, you’ve chosen one, or a set that are related, and then you have set some priorities in regards to, oo, this one is … you always say, Allen, has the biggest juice, has the biggest impact, maybe costs the least. It’s something that can easily be done and implemented, and then have a better set of results than maybe something more complicated, right?

So, you’ve set … You’ve chosen the idea, or set of ideas, set the priorities in relation to which one has the most juice, and then the solution, potential solution, to that problem.

Allen Fahden: Yep, now it’s time to run the WHO-DO method, and that’s with the whole team. Now, there’s one little tricky piece here, not that tricky, but the makers usually don’t want to be there, because they want to be away from the meeting doing real work. So, they can attend if they want to, certain, but probably they won’t want to.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and if they do attend, remember, they take that prover role on, because they’re still later adopters, so …

Allen Fahden: Right, and they can … Like the prover raises objections, they can raise objections, just at a more granular level.

So, once you gets the provers and whatever makers want to participate, they get to poke holes in the ideas for the solution to the problem, and that’s a beautiful thing to do first, and they love doing that because nobody’s going to push back at them. What we do is we put brainstorming rules in effect, and you can’t say that’s a bad objection, you can’t argue. And you simply have the provers have their way with it, poke every hole in it, warn about everything that can go wrong.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and in addition, you may or may not, in this stage, have to run the full WHO-DO. And what I mean by that is you can start at the prover. So if you’re pretty clear that it’s a … maybe it’s an obvious problem and solution, something easy to do, then you can go in and just start poking holes in it, right?

But that might not be the case, depending on either the innovation, how, you know, difficult the problem and solution is to implement, right? So keep that in mind, that if it’s something that is easier, when the provers come in, you can jump at going through brainstorming, shakers coming up with ideas, movers setting priorities, that you can just go right to the proving at that stage, too. It can save you some time if you don’t need to, you know, do that. But it really depends on the difficulty, and the clarity, of the problem and solution.

Allen Fahden: If it’s … If the problem requires an obvious solution, it’s cheap, it’s easy, it’s fast to do, it’s something you can do right now, great, go ahead and do it. The other thing is you may need something that’s more proprietary, you may need something that blows away the whole even need for a fix like that, and that’s when you get the shakers in for ideas.

Karla Nelson: And you know what’s interesting about this, or, and this is where we’ll give you an example of, you know, getting a solution statement, if you have a team that is not really well trained in the WHO-DO, a lot of times what you’ll have to do is go back to the drawing board. And then you’re like okay, you haven’t really clearly identified the problem, or you’re going to something so obvious that it’s status quo, this is what we’ve always done, then a lot of times, even if it’s an obvious problem, and you’ve made a solution, the solution might not really be attacking the root of the problem because you’re not going deep enough.

You should tell the example.

Allen Fahden: For example … For example, we were in the training one time when people said, “You know, what we … we’ve identified the problem, and the problem is our signage isn’t good enough. We need more signs. We need better signs.” Now, that-

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and this is in a place that has more signs than you … than you ever need, and it’s … it’s just hard to see anything because there are so many things flashing in your face.

Allen Fahden: That’s right, so now it’s interesting, because that was the statement of the problem, we need more signs. Now, if you take the words we need off there, doesn’t that sound like a solution? Hey, more signs, is actually a statement of the solution, so what was the problem? Why would you need more signs? You know, so you ask why. It’s a quality question, and once you do that, you back it up into cause, and you say well, because nobody can get around, they don’t know where they’re going. Okay, now that’s a … probably a much better problem statement.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and they went through and then went, “Oh, okay, the problem is people are lost,” right? That’s the problem, people are lost. So what the solution actually was is people are found, it wasn’t that we need more signs. So they had to start the process over, so when we facilitated it, identifying that. But it was the first time that you’d used the methodologies-

Allen Fahden: And they came up with a solution that was far cheaper, far faster to implement, and-

Karla Nelson: Better.

Allen Fahden: Far more effective simply by correctly defining the problem, and that’s what the WHO-DO overlay did.

Karla Nelson: You got it, and you … The tool that we use to get them out of their normal way of thinking, which it wasn’t that we need more signs, it was that people are lost, then go to the opposite. So, you can refer back to the last two podcasts, that what we talked about, the obvious to opposite, and then there’s five steps that you can go through that.

And using that tool they were … Because we didn’t give them the answer, because then they wouldn’t learn, but we gave them a tool and said, “Use this,” and it changed the way that you think about it. And so, again, we did the last two podcasts on that too, so you can refer back to them if that’s something that you want to do.

Allen Fahden: Yes, and after you run the WHO-DO, or if you have to do a modified WHO-DO and begin with the provers telling you everything that can go wrong, well, then you’re ready to move to the fourth stage of design thinking, which is prototype.

Karla Nelson: Prototype!

Allen Fahden: Prototype.

Karla Nelson: Prototype always feels good because you feel like you’re actually getting something accomplished.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, right.

Karla Nelson: So-

Allen Fahden: Let’s do something!

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and by the way, there’s where … That is exactly what you just said. Look, most people skip the first two steps, do a poor job on the first, and then they run right to the prototype. And if it’s expensive prototyping, the first … Or they try to do everything, right? They try to have the complete solution in the prototype.

The prototype is just where you get the provers and the makers, right? You bring them into the picture, right? And then … And, so … And just create that clarity around, okay, how are we going to build something that somebody could look at so you can move to the next stage.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, and they are focused, and live in reality, and that’s the beautiful thing about the prover, because they are a great leader in this place because you … as a prototype, you’ve got to get something that people can react to in the real world.

And the mover needs to oversee it, though, because what you don’t want to do is throw … is throw out all kinds of things because they have so much wrong with them. So, it’s the mover who can help make sure everybody stays on strategy, and to ensure that rapid prototyping is rapid enough, and that the makers will be naturally focused on a complete solution. So they can do the details, but-

Karla Nelson: Yeah, but … And you don’t want it to go too far.

Allen Fahden: … we don’t really need that.

Karla Nelson: Yeah.

Allen Fahden: Yeah.

Karla Nelson: You don’t need that yet, in this stage.

Allen Fahden: Because it can be crude.

Karla Nelson: … prototype.

Allen Fahden: It can be crude.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, this thing, it can fall apart. It could be-

Allen Fahden: Yeah.

Karla Nelson: There are so many different ways of … depending on the problem and the solution, you know, how you could prototype that. The biggest thing is, you know, you … It’s just a critical part of design thinking is rapid prototyping. They even should say rapid, just so you know. This is not perfect, right? But when-

Allen Fahden: Right.

Karla Nelson: … you have a rapid prototype, and the best product people always have six, seven prototypes, because they’re getting better, they’re getting feedback, right? But when you do the rapid prototyping it saves you time, money, energy, especially in technology companies, my goodness.

So, after the team comes up with the prototype, okay? Something, doesn’t have to be a full solution, it’s time to then move to the fifth stage of design thinking, which is test. So you … It’s time to test the prototype.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely, and this stage is led by the prover, again, with the assistance of the mover, again. And the point, in this stage, is to figure out everything you need to know in order to get the solution implemented.

Karla Nelson: And then you have to look at that both from an internal or, you know, external, or both, right? Depending on the type of the problem, right? I was just talking about, is it a technology? Well, is that technology internal? Is that technology external? How do those potentially … You know, you have to look at that from the big picture standpoint when you’re looking at implementation, right?

Allen Fahden: Absolutely.

Karla Nelson: Because you could implement something internally and it effects externally, or they could be completely not related.

Allen Fahden: Yep, and testing is dependent on the problem and the proposed solution, but regardless of what it is, you’re going to want a prover leading that. Now, one thing I want to just jump back to is that, you know, if you’re doing a service or something like that, building a prototype could be as simple as drawing some pictures on a big sheet of paper, just so that people can visualize what you’re talking about. And, so-

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and remember, you have to have your mover assist here, right?

Allen Fahden: Yep.

Karla Nelson: Because you don’t want to kill the idea.

Allen Fahden: That’s right, the mover then keeps focusing on the possibilities, keeps moving it ahead, won’t let it get stuck in the mud, because the prover is a lot more likely, natural, natural instinct, to kill the idea. Mover will look to the shaker, if necessary, on how to keep the idea live, because the shaker is really motivated to do that, and then jump over any hurdles that come up, and shakers-

Karla Nelson: Yeah, shakers motivation-

Allen Fahden: … are really good at dancing and jumping.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, exactly, and then it insulates it, right? So you’ve got the prover who is dealing with reality, and then the shaker who likes that input to go, “Oh no, look, we can solve it this way, this way, this way. We can do this. We can move this over here.” You know, and so that’s critical to have that mover keeping it going, but letting the prover do their work so that you can get the feedback that’s necessary.

And hey, sometimes the idea does get killed at this standpoint because there is too much wrong with it, right?

Allen Fahden: Yep.

Karla Nelson: And that’s great, because if that’s the case then, you know, you’re killing the idea in concept form, not after you put a whole bunch of time, energy, and money behind it, right? And that’s why you do rapid prototyping, so you can move to the test phase and get that feedback that you need.

So now that brings us up to the final stage that we added to design thinking, right? So … Because you can’t … What are you going to do, just, like, test the prototype and … I mean, you’ve got get it implemented, right?

Allen Fahden: Yeah.

Karla Nelson: So, again, the final stage of design thinking that we added, the WHO-DO added, which is share, because you got to sell this idea.

Allen Fahden: That’s right, because it’s not going to go anywhere unless you sell it, and, now-

Karla Nelson: And again, I want to jump in here, selling internally or externally, hey, selling an idea to the team, or a solution to the team, is the same as the client, but for some reason we only think when we sell we’re selling externally to our clients, and you have to start with your team.

I don’t even care what it is, because if it’s a marketing solution, or a sales solution, you still have to get everybody on board. You have to sell it to your supervisor, you have to sell it to, you know, whoever you need, whoever has to approve the budget for it, right?

Allen Fahden: That’s right. So, now it’s interesting, too, because this is where it gets really powerful to overlay the WHO-DO method on this, because whether it’s external or internal, they’re each … each person has a different way they want to be sold to, whether they know it or not, this is based on their core nature.

So, let’s start with … and this could be somebody on your team, or it could be your boss, but-

Karla Nelson: Yeah, we just had a call with a client that brought this exact thing up, right? Like, when you’re a hammer you think everything is a nail, and-

Allen Fahden: That’s right.

Karla Nelson: … we think everybody that is like us, and then … and of course, that’s the only lens we have is our lens. But it’s really critical, and if you can, right? If you know who you’re selling to, whether a mover, shaker, prover, or maker … Actually, Allen, let’s just take a second and we’ll go through each, right?

Allen Fahden: Yep.

Karla Nelson: So if you’re selling to a mover, then how should you respond?

Allen Fahden: So, when you’re selling to a mover what you want to do is bring several ideas and say, “Here are some of the things we’re working on, and which makes the most sense to you?” Now, you may already know, you know, what you’ve done, what you have tested, but the mover wants to look at all the ideas and make sure that that’s the one they want to run with.

And then it’s always asking … a mover, you always ask a mover for what’s next. They’re great at next. So ask them, “How can we move this ahead?” But first enroll them in it, and that’s like, you know, here are all the ideas, this is the one … these are the ones that tested the best, and we’re thinking about doing this, what do you think?

Karla Nelson: I’m already one that said-

Allen Fahden: So, people buy what they build.

Karla Nelson: … yes to your idea.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, that’s right.

Karla Nelson: And then, you know, and sometimes with a mover, if it’s really obvious, or you had a mover facilitating the problem and solution, just go back to all the ideas, because even if they scan the ideas, they feel like they were a part of choosing the best ideas.

So, just hit a slight rewind and give them the back view, these were all the ideas, we did our homework, and then this person picked this one because of these reasons, and then we prioritized it here. So, just hit rewind a little bit with the mover, because you want them to see all the ideas.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, it’s an interesting thing, because when you’re selling, in a sense, you’re going back to empathizing, but now you’re empathizing … you know, that was the first step in design thinking, but now that you’re empathizing with the person you’re selling the idea to, or you’re sharing the idea with, so-

Karla Nelson: And remember, this is both sides, internal or external.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely.

Karla Nelson: Right?

Allen Fahden: So now if you-

Karla Nelson: Go ahead.

Allen Fahden: If you’re moving a … or if you’re selling an idea to a shaker, let’s say your boss, or the next person who needs to approve this, or who needs to buy this, is a shaker, then what they love to do is they love to A, solve problems, or B, come up with ideas, and of course both of those require coming up with ideas.

So, one of the things you can do when you’re selling to a shaker is show them the problems you were looking at solving and let them come up with ideas. Now, the beautiful thing about that is if they can solve the problems, and it may even be a problem that a prover has raised with your solution, let them contribute their own solutions, that way they’re doing exactly what they want to do, which is imprinting the idea and making it their own. Shakers love more than anything to have a big idea be their idea, and if they can’t be all their idea, then it can at least be partly their idea.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and then, again, you can use a strategy of hitting rewind and asking the ideas from there forward. So you can get the ideas, and get them to imprint it either by rewinding, very similar with the mover but you do it in a different way, and then fast forwarding and enrolling them into the next step.

So, depending on what you have, because, of course, we’re talking about this in real general terms, because you could be … a problem’s solution … I mean, gosh, there’s millions and problems of problem solutions, so a lot of times if you hit rewind you can also start that from that point of pitching, presenting, whatever it is.

Allen Fahden: Okay so we move to the prover and I want you to keep your finger on the rewind butter, because it’s the same with the prover, but you rewind in a different way. To the prover you say, “Here are … Here’s the idea we looked at, and here are some of the problems we found with it, are there any more that you can warn us about? Any more things you can see going wrong here?” And if they contribute one, fine, you can always go back and help solve that particular problem. And if they say no, you’ve pretty well done it. Well then-

Karla Nelson: Then you really got a cheerleader on your team.

Allen Fahden: That’s right, because that’s … a prover loves to see more detail than the mover or the shaker, because they really want to be able to pick that idea apart so they can identify any trouble spots. So again, it’s a different kind of rewind, you take the idea apart and show it to them, and you show them the problems, you know? Show them the dirty laundry, because that’s what they want.

Karla Nelson: And remember-

Allen Fahden: They love that.

Karla Nelson: … they’re the leader on the implementation. So after you’ve done all this and everyone decides, okay, we’re going to do this, your prover becomes your point guard, and you want to enroll as many point guards, because they’re the true implementers that can be patient enough, then, to …

Let’s move on to the fourth one, which is the maker. How … If you’re selling to a maker, what should you do?

Allen Fahden: Yes, well, the first thing you should do is don’t sell anything.

Karla Nelson: I was just going to say that.

Allen Fahden: Because what the maker wants to hear is that you are aligned with that maker in protecting the system, in protecting the routine, because right now everything is running smoothly, and it will be a real upset if you’re going to bring in anything in here that interrupts that.

So, one of the things that … You know, it’s like, I’d spend 80% of the time selling the maker on the fact that we are going to be so sensitive, so that anything we bring in here is not going to interrupt the status quo. And if it even looks like it is, then together we’ll solve that and make sure that we take all the right steps to make sure there is no interruption in the routine, and there’s no disruption in the results that the maker is creating.

Because that maker is finishing things, or creating not only, well, profitability, but they’re making sure that, you know, the whole organization can deliver on its promises, and so-

Karla Nelson: Yeah, I love how you identify the profitability piece with the maker, because they’re … it really is the repeat process. If you don’t get to the repeat, because you need to innovate on the front end, but you also need to repeat, and keep that repeating going, even as you’re bringing new innovations in, without disruption.

So without those later adopters … You know what? You should tell the story in regards to the client that, coming … All the buyers, that are almost always later adopters, buying products. The one buying phone systems.

Allen Fahden: That’s … Yeah, so a big telecommunications company used this, and one of the things they found out was that their customers would always assign a team to buy, because it was a big purchase, to buy their phone systems from them. And so, we tested them, and we found out that they were all provers and makers. And it makes sense, because why not? They’re doing the due diligence. They’re the late adopters, that’s … You know, of course you’d have them buy, you know? You want to make sure that, you know, they’re not running off-

Karla Nelson: You don’t want to give the shakers the … a checkbook, and movers don’t have ability to see the detail.

Allen Fahden: That’s right.

Karla Nelson: … they know in that place, they know they need it, but they don’t have the ability to look around the corner and say, “Oh, man. That’s not going to work, and if we get that system …” you know, all … That piece is super important when you’re spending millions of dollars on a phone system.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely. So, it’s … However, you know, with that blessing of having the due diligence in the hands of the later adopters, it also comes with the accompanying curse, which is that the later adopters, when they get under stress, their instinct is to go to early behaviors, which is just to, you know, shut it down, we’re going to have to put this on hold.

And so, what the phone company did was said, “Okay, we’re going to help you get out of one of your scariest positions, and we’re going to help you buy the ideal phone system for your company. And we’re going to make sure you guys perform for your management, because we’re going to add movers and shakers to your team, and then run the process. And so-”

Karla Nelson: I mean, that’s just brilliant, right? You got the later adopters who are scared to make a move, and you need to get the sale, and you need to take care of your client. You want to help support them, so you bring in the movers and shakers, right? And now you’re alongside your client. You’re bringing in the part that they don’t have that gives them the … you know, the feeling that, oh, it’s going to be okay, right? That the scary-

Allen Fahden: Yeah, just … Oh, they’ll take that part over, don’t worry about it. And the beautiful thing is the way they defined it. They said, it’s not we’re putting together a team to sell you a phone system, they said, “We’re putting together a team to help you buy the ideal phone system for you.”

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and by the way, if you ever said that to a mover or a shaker, they are happy with running a process, but … they would never even want that job. I mean, it’s just a slight shift, right? In how you talk to them.

And Allen, just to iterate for the listeners, I’m sure depending on how long they’ve been listening to the podcast, they understand early or late adopter. But explain how you can, if you, you know, are working with a customer, and you’re not sure who they are, kind of, like, how you get a sense for who they are. For us, we’ve been doing this forever, and we can almost guess. We can get close, at least on the early adopter, right? The do think is a little bit more challenging, but the early, late adopter.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, so early adopters, you know, there’s 110 years of research on this, is … called diffusion of innovations. However, what we did was took that inside the organization. It was always, you know, a consumer thing, this is how you understand consumers, but people are the same way when they’re working for an organization, or they’re buying something in business for their organization, that’s just a core nature, is are you an early adopter or a late adopter.

Early adopters are people who are very much into possibility, how things can be, they’re enthusiastic, and they fall in love with an idea. You know, as a consumer, I am the idiot who stood in line for eight hours to get the very first iPhone. Wound up paying $200 too much for it, and I was happy, because I had it for two months longer than anybody else, so I didn’t care. And so, that’s how early adopters think, and they’re always wanting to bring new ideas to things, new thinking, and then move that thinking ahead.

Whereas the late adopters are very much more, by contrast, into reality. They’re the ones who are more … are more practical, more conservative, and even more skeptical. They say a laggard is a very, very late adopter who still has dials on their phones and wouldn’t buy an electric car until the last gas station in America was closed.

So-

Karla Nelson: That’s awesome.

Allen Fahden: … we’re very, very different people, and one of the things we’ve done is found a link between the early and late adopters, and that’s between the mover, who’s very practical about moving ideas ahead, and the prover, who wants to tell people what’s going to go wrong, and the mover wants to know that. So that’s a very viable relationship. It’s like an entry point from early adoption to late adoption.

What you want is that if a team is missing one of the four, it’s in trouble, if it’s missing two of the four, it’s a disaster. So we need us all. As you say, we need us all, we just need us at different times.

Karla Nelson: I love it, awesome. Well, I think that brings us to our conclusion. We’re really excited, we’re going to start looking at other methodologies that are used, and how the WHO-DO overlays with it. So if we’re already using a methodology, or some type of an assessment, you can overlay the WHO-DO, because again, it doesn’t redact anything from what you’re currently doing, it just puts gasoline and a match on it. So, anything else you’d like to add, my friend, before we sign off?

Allen Fahden: No, I think we should put gasoline and a match on signing off.

Karla Nelson: Woo Hoo! Awesome. Alrighty, well, I will see you soon-

Allen Fahden: Thank you.

Karla Nelson: … my friend, and thanks to our listeners out there, and we’ll see you the next time on the People Catalysts Podcast.