The WHO-DO: Deep Dive

Who are you? Are you a Mover or a Shaker? How about Prover or a Maker? Or one of the rare few “Oners’ in the world? In this episode of The People Catalysts, we dive deeper into what your core ability really is. After all, Sun Tzu said “know the enemy and know yourself; in a hundred battles you will never be in peril.”

Listen to the podcast here:

The WHO-DO: Deep Dive

Karla Nelson: Welcome to The People Catalysts podcast, Allen Fahden.

Allen Fahden: Hello Karla?

Karla Nelson: Good evening kind sir. How are you today?

Allen Fahden: It’s a great day. I’m just back home from extensive travelling and I’m so happy to be home.

Karla Nelson: No kidding. This last month is extensive, extensive, extensive. I still have two more trips. I am not terribly excited about it. But we definitely love making a difference in the lives of the people we have the opportunity to serve, that’s for sure.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, because when you’re there it feels great. It’s just getting there and coming back.

Allen Fahden: Getting back isn’t good.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, we were in Vegas for five or six days straight and Allen was like, “Yeah, I had to quit smoking when I got back home just from walking.”

Allen Fahden: Yeah, just from walking through the halls of the hotels.

Karla Nelson: What we are going to talk about here today on the podcast is, and we really been talking about rewinding a bit and where do you start? Because again, the Who-Do method, while it is very simple, so is climbing to the top of Mount Everest, put one foot in front of the other, but I would venture to say it’s not easy.

So as you use the method you just got to add a deeper level, and a deeper level. Then you can start overlaying different technologies with it, which is by the way, what we’re looking at doing with same design thinking and with six sigma and some other corporate methodologies because the Who-Do method gives you the ability to put gasoline and a match on whatever you’re already doing.

It doesn’t redact anything and it’s not in competition. It’s basically just putting people in the right place, at the right time, doing the right thing and having them lead the portion of the work that they do best.

So what for today’s podcast, we are doing our first webinar cell podcast. So I know some of you listening in your vehicles you won’t be able to potentially see the visual screen.

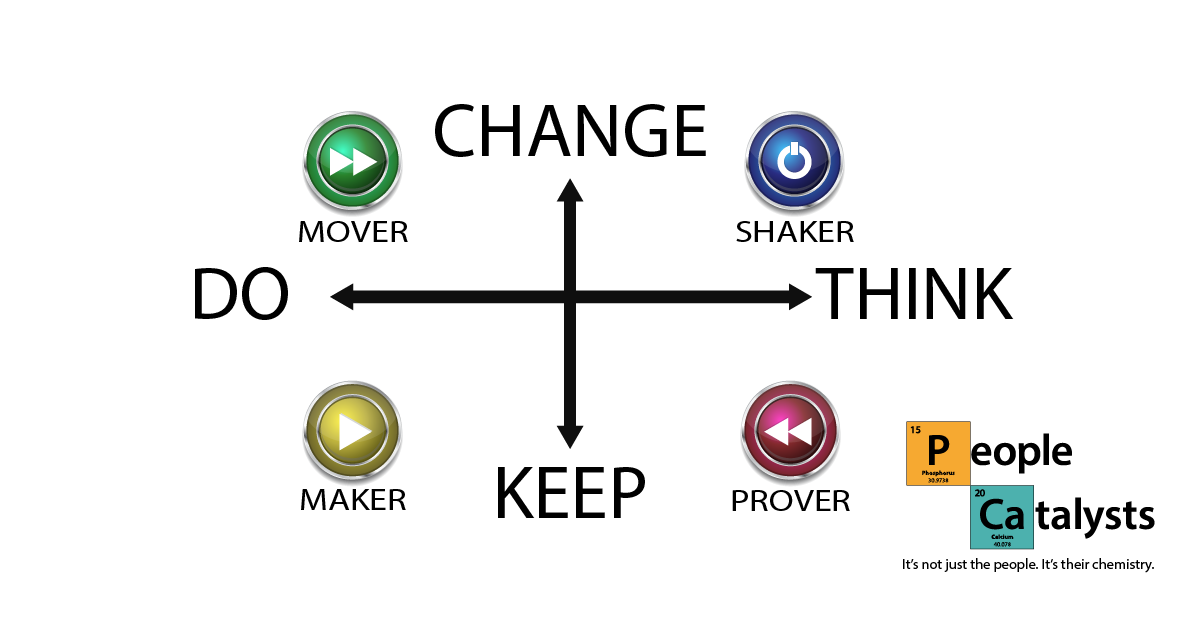

However, for those that might be watching it on either social media avenues or that you do want to look behind the screen and see the visuals that we are giving people. Because sometimes … And we’ll prompt what the visual looks like, like the X and Y axis that you’ll see a little bit later on that we’ve talked about so much with the do-think early, late as an adopter. So we’ll help you with that.

The design of this podcast is so that we can go let’s rewind it to the very basic part of understanding why the Who-Do method works. One thing, Allen, I’ll make a note of, is that we also include the law of diffusion of innovations. We talk about it all the time, 110 years of marketing research. You can just read that even on Wikipedia. But understanding why that methodology laid over with do-think and early and late.

So with that said, Allen, how about this, you go ahead and control the slides and then when there’s a time to jump in, I’ll play the audience and then also piggyback on some of the things you say, because sometimes it’s hard to present this particular shorter version. We’ve even got many different versions, all the way 20 minutes, 45 minutes, an hour, all the way up to four hours that we just did recently in Vegas. How does that sound Allen?

Allen Fahden: Sounds great.

Karla Nelson: Fantastic. So just take it away, Allen Fahden.

Allen Fahden: So we started with The People Catalysts because this is important that we’re giving you here today is a view of people that you have perhaps never gotten before if you’re not familiar with the Who-Do method, and that’s we call it the people catalysts.

We’ve even got the P in people being the chemical symbol for phosphorus and the C-a in catalyst being the symbol for calcium. And our point is it’s not just the people, but it’s their chemistry, and that’s what happens when you fit people together.

Karla Nelson: Yeah. Then we found our mixing phosphorus and calcium together, it creates bombs.

Allen Fahden: Yes, they do.

Karla Nelson: And fireworks. That’s kind of cool, fireworks.

Allen Fahden: It’s a new interpretation of putting gasoline and a match to your project.

Karla Nelson: There you go.

Allen Fahden: There are a couple of ways to do that. We recommend the kind that is the accelerator and not the explosion. So, then we all want to start out with a $2 bill. The $2 bill is just kind of an interesting symbol because it’s money that really nobody wants. It’s never been successful in the United States. So, we always ask people, “Why do we carry $2 bills?”

Karla Nelson: Yeah, but you’re going to have to come to one of our live trainings to see this in action. This is totally fun and in regards to the $2 bills, and the purpose is how do people respond differently, right?

Allen Fahden: Absolutely, and that is the lesson and there’s some goodies as far as learning goes. Again you’ll not experience it this time, but what’s important here is that what it shows is that you can give the same stimulus to different people and you’ll get a completely different response. So the three words to remember from this and really from all this is that people are different.

Karla Nelson: No.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, it’s just what a surprise, right? So it’s a … and you might even get paid $2 for finding out one of these days.

Karla Nelson: Or even more than that.

Allen Fahden: Or more than that because we hand out $2 bills at our seminars.

Karla Nelson: What was great is that the other training when the CEO walked over and gave them $50 bills for the $2 bill, that was a fun one, right?

Allen Fahden: Yeah.

Karla Nelson: He’s definitely an early adopter.

Allen Fahden: That was happy because actually the two does look, if you have upside down and backward dyslexia, the two looks kind of like a five.

Karla Nelson: There you go. So Allen, if you also want to talk a little bit about why and the people on the back of the $2 bill and why it makes it very interesting.

Allen Fahden: So it’s the only bill … If you look at the back of a $20 bill it’s got a picture of a building on it, and if you look at the back, well $1 bill it’s got O-N-E on it, and most of the bills have the buildings on them, the Lincoln Memorial, the Treasury Building and et cetera. This is the only bill with people on it.

So I ask people, “What is this a picture of?” And it’s got all the founding fathers standing there at a desk and it’s actually the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and I call it the first dysfunctional meeting. One of the things you’re going to need to do is to attend one of our seminars and find out why it’s the first dysfunctional meeting. But I’ll tell you this, there have been an awful lot of dysfunctional meetings since then.

Karla Nelson: Yes, or you could also be licensed in the Who-Do method. We made that available this last year. It’s been really cool to train other trainers in the methodology without redacting anything they currently do.

Allen Fahden: Yeah.

Karla Nelson: Again, just putting gasoline and a match on. I actually had the opportunity to meet with one of our favorite trainers just this morning.

Allen Fahden: Yes, indeed. So and he-

Karla Nelson: Most people don’t … Go ahead.

Allen Fahden: No, I’m just saying and he keeps taking it to new areas. So he’s a wonderful guy and very smart.

Karla Nelson: Yes and one … Also, the other thing about the Declaration of Independence, most people don’t really know that, which I find fascinating. Don’t you find that fascinating? I have hundreds and hundreds of times doing this both there’s people on the back but the fact that 33 were like we’re fine with the British, 33 wanted to launch the United States of America and 33 just weren’t anywhere … have anything to do with it.

Allen Fahden: Yeah.

Karla Nelson: Lucky guess which one is the late and early adopters.

Allen Fahden: Yes, that’s right. And meetings continue to be like that today.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, exactly, and what is that called? It’s called good luck.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, it’s good luck.

Karla Nelson: It’s good luck, and there you go on the misfits’ wheel of misery, right? The three dises.

Allen Fahden: Yes, disagreement, and that’s what meetings are set up for. Disappointment, and that’s what work is set up for. You give somebody an assignment and they come back with something completely different or they come back later or they don’t come back at all. Then of course if you have disagreement and disappointment, that leads to, ta-da, disengagement and disengagement is enormous today.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, it’s huge. The number is so crazy and they’ve been putting billions and billions of dollars at that challenge for over 50 years and they still wager right around 70%. Complete losers as far as getting something done. Well think about it, you’re not solving the reason why people are disengaged. You can’t just look at somebody and say, “Stop being disengaged.” It doesn’t work.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, “I order you to be no longer disengaged.”

Karla Nelson: Yeah, try it, let me see how that works out for you.

Allen Fahden: If that works, I got a $2 bill for you or maybe a three or a four. So moving on, people are different. That’s the thing that we are setting up, and it’s important to know how they are different. So there’s really two ways in which they’re different and that’s what makes this model different from just about everything that’s been before.

It’s not a personality assessment like a Myers–Briggs or a disk, because what it does is it measures two different factors. One is are you an early adopter or a later adopter?

That’s always been a consumer tool and what we did is we brought it into the company and we said okay, you can be an early adopter inside the company, you can be an early adopter at work but it’s being an early adopter of ideas rather than products or services.

So if you get behind an idea earlier, you’re an early adopter, you want to change things. Or if you’re a later adopter and it’s about 50% or misses 110 years of research and the diffusion of innovation, the way it goes is 2.5% innovators, those are the earliest of adopters. 13.5% are early adopters, that adds up to 16%, which is about the amount of people who have what’s called an internal locus of control, match to the beat of your own drummer. 34% are early majority. Those three add up to about 50% and those are the early adopters who like to change things.

Then you have later adopters who like to keep things as they are. You have 30% late majority and 16% laggards. Of course there are a lot of laggard jokes that a person who wouldn’t buy [inaudible 00:11:20] until the last gas station in America was closed, and the person who still has dialed on their phones.

So, that’s backed by 110 years of research and obviously if you’re going to do something that’s either change or innovation, you want to go to the early adopters first. Well, for the first time now you can identify your early adopters.

Karla Nelson: Yeah.

Allen Fahden: You can identify your later adopters and know who’s going to be motivated to do what. But then you have another thing-

Karla Nelson: Also …

Allen Fahden: Yeah, go ahead.

Karla Nelson: Before you jump on to the next thing. First of all, for the listeners, we’re going to think about the X and Y axis. So the change is at the top, the keep is at the bottom and the do is to the left and the think is to the right.

So it’s … The other piece about that in early and late adopters is everybody understands that when it comes to finding your customer, the big challenge businesses have is they don’t do it internally but yet expect everything to be working well so that you can then have your team reach out externally to the early adopters and market to them.

So, that doesn’t make any sense. You have to start with your team. Then you get that working well, the team reaches out to the clients. Happy team, happy customers, and then we haven’t quite gotten to the promoters. We’ve done that in a previous couple podcasts. So get this done internally.

And it doesn’t mean that you have to have a team of 50 people. Even if you’re a solopreneur, you better understand who you are and how to put people around you that will fill in the gaps of what you really basically stink at.

Allen Fahden: Yeah. So, let’s move from change to keep. So change to keep, that’s early and late adopter, those are great inboxes for people because they … You know that an early adopter is going to be motivated, “Let’s change things or do something new here.”

And a later adopter is going to be motivated by, they’re going to want to work on something that refines the status quo, keeps things the way it is, makes the routine better. So innovation is for early adopters, quality is for later adopters. It’s all about making the system incrementally better.

So then we move to do and think. Now, there are, if you’re a doer that means that you can take something and plot it out in sequence. You can think sequentially rather than randomly. Doers think sequentially, thinkers think randomly. So a doer says they can put one foot in front of the other, they can get one, two, three, four, five done. Whereas a thinker will say squirrel and they’ll be-

Karla Nelson: Ping, ping, ping. That’s probably one of the most frustrating things. I love everybody. Of course we all have our different gifts. The thing about the shakers and provers, which are thinkers, is they’ll just randomly start just working on … They’ll potentially make the checklist or never make it at all.

But they’ll start working on something that is not even important and not knowing, like for me it’s obvious, right? You put it in order and actually [Steven Curvy 00:14:36] teaches that. That’s the A1, A2, or B1, B2, and then you start that way.

But what happens is you … they just randomly change. One of our team members we work with all the time is a prover-shaker and it will be like I’ll ask a question, he’ll stop doing everything and start working on this thing I just asked a question about. I’m like, “I didn’t ask you to stop everything, I just wanted your input on something so I could work and do something else.” Which is kind of funny because for a mover and a maker, it really is a very linear, logical way of taking tasks and breaking them down.

Allen Fahden: Yeah. So how this differs from personality is just very simple. From personality profiles it’s are you a thinker or a feeler and are you people-oriented or task-oriented, whatever the motto might be. That’s usually about what’s your … how do you show up in meetings, what do you like to be around?

Whereas this is what parts of the work should you do? What do you do in your strengths? What are you fast at? What are you great at? When do you hit it out of the park? That’s what we’re … this is about finding out what the right role is for the person.

So if you take, for example, you take … If you’re a changer, an early adopter and a doer, you’re a mover. A mover is a person who’s like a point guard on the basketball team. They can run innovation processes, they are great at setting priorities, they can make, you give them 10 ideas, they’ll say, “Oh, we ought to do number five first but we got to do seven beforehand because seven drives five.”

Then they can make a plan, “I can get that done in two weeks and we got a budget over here. We’re going to talk to so and so. I’ll need to talk to these other people here.” They can see the whole thing unfolding in their mind’s eye. So they’re a great planner and they’re a great runner of the part of the team when it’s time to get something done.

If you go to the other side as far as the early adopters and you go to the thinkers, then you’ve got a shaker. A shaker is a person who likes to shake things up. The symbol, by the way, for the mover is the, for those of you who can’t see the visual is it’s a fast forward button on a remote.

They can make things go really fast and really well, whereas a shaker is more the on and off, the power button. It’s the shaker who provides the ideas. They are thinkers and they are early adopters. So they love to generate new ideas, they love to solve problems.

So those are the two early adopters. Now, you don’t want to stop there because what you’ll do is you’ll go off half-cocked and do something crazy with them. They won’t even think about what can go wrong. That’s why there’s a person called the prover. The prover has got a symbol of a rewind button.

The prover says, “Hold on,” they’ll rewind the thing and say, “You forgot about this, you forgot about this, you didn’t think about this.” Then they think ahead and they say what can go wrong here and that’s illegal in 18 states. And it’s a beautiful thing if you put the right people in the right order, doing the right thing at the right time because the shaker then can come up with ideas to overcome the barriers that the prover raises. So these three people make a great innovation team.

There’s a third or a fourth person, excuse me, a fourth person who’s a later adopter and a doer, and that person doesn’t even want to be in the meeting. Their symbol is a play button.

They like to run the routine, don’t bother me, you’re just going to make me uncomfortable if you’re talking about doing all this new stuff because it’s just going to disrupt everything I’m doing. So that maker doesn’t even want to be in the meeting but they’re a great finisher.

Karla Nelson: I love that, by the way. They laugh. That is something that as soon as you say that, “Who just doesn’t want to be in the meeting,” and they laugh and we’re like, when you show it to them they’re like, “Oh my gosh, that makes so much sense.”

Allen Fahden: Yeah, how many-

Karla Nelson: Because they got to do the real work thing.

Allen Fahden: That’s true.

Karla Nelson: They got to go eat their checklist sitting at their desk.

Allen Fahden: When you say, “How many makers are there in the room? Raise your hands please.” So let’s say six of them raise their hands. “And how many of you don’t want to be in the meeting at all?” All six hands stay up.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and they just want to be okay with that too, which is … And it should be, right? In the beginning on the innovation and what we call ideation piece, they don’t really need to be in the room.

Allen Fahden: No.

Karla Nelson: It hurts them to just think about all this stuff that they’re going to have to do because they just cleaned this place up man, you’re going to come in and mess it up again.

Allen Fahden: That’s right, and you know what? Each person, no matter how different they are, has something in common and that is they all want to be valued for who they are.

So Karla you just talked about what the maker wants to be valued for is respect that I don’t want to be in the meeting, I’ll be doing real work, you need something finished, I’ll do it elegantly, and don’t bring me a bunch of new ideas it’s just going to upset me and it’s just going to disrupt my routine. The prover that doesn’t want to be known as the buzz killer.

Karla Nelson: Eey-ore.

Allen Fahden: Eey-ore

Karla Nelson: A naysayer.

Allen Fahden: So many provers have come up once we run the Who-Do method and say, “Oh my gosh, I can’t believe you allowed me to rip an idea apart and then everybody smiled about it and I was close to a hero for doing that?”

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and here’s a key piece and there’s a key piece of all of these different core natures of work, mover, shaker, prover, maker, but one of the things about a prover is that they, although, you don’t begin there at the prover, they are a late adopter. If you convince them it is a great idea and you shave all the hair off the deal, right, that’s what we always used to say when we were raising capital for businesses.

Allen Fahden: Yeah.

Karla Nelson: Then you’ve got a confidant that is great at killing things an idea concept, an idea foreman and if you can unleash that, they are so happy but they are like right there. Then the provers, the one who is patient enough, because neither the mover nor shaker is patient enough to work with the maker.

Allen Fahden: Right.

Karla Nelson: It’s just straight red light, not going to work. Whereas the prover and the maker can get the implementation piece done just with the mover and the shaker. You’re never going to get to the end with spending at least a decent amount of your time doing what we call peak work. You’re going to have to do week work if you’re asked to start it, pick the best idea, run with it, and then continue to repeat it.

So, a prover and is in that regard … There’s a crux in every piece and we had a previous podcast too that anybody who’s listening can go back and listen to the red light and green light relationships. But it’s just critical I think, and that’s one of the things, when the ahas on so many of the meetings we’ve done. Allen is, “The prover isn’t so bad after all. You just kind of feel bad for them.”

Allen Fahden: That’s right, and in fact everybody is in their own period of time a hero. And it takes us all, as you say, it takes all of us just at different times.

Karla Nelson: Yes.

Allen Fahden: Now, there’s one thing I want to do is presence one more person, and that is a person we call them a oner. That person is an equal balance of mover, shaker, prover and maker.

That’s a oner because they’re 1% of the population, and the irony is … Now think of a person as a utility and filler. They can play any part, they just don’t do it say, as extremely or on perhaps such a level as somebody who’s all of one thing and has done it all their lives.

But they’re a great fill in for if you’re missing a team member and then they’re also the 1% of the people who can do the work the way it’s structured today and it has been structured for 150 years. In other words-

Karla Nelson: Yeah, and that’s just bringing 100% of the work made for 1% of the population.

Allen Fahden: 1%.

Karla Nelson: To be super successful.

Allen Fahden: That’s the person to whom you say, “Hey, nice idea. Why don’t you run with it?” Well they can. It’s a person who says you started it … you say that to them, “You started it, you finish it,” they can. The other 99%, they can’t, and that’s what wrong with the work today. That’s the one percenter.

Karla Nelson: All right, so moving on.

Allen Fahden: Moving on, this is what happens to people in their jobs is they wind up spending, doing about 10% of their peak work and about 90% of their week work. So that’s just the way things naturally are. We’ll say a little bit more about that later. In fact, we’ll challenge you with a little bit of a quiz on that.

But just know that the way work is set up today, we are doomed to fail and if something actually works, it’s a rarity and that’s why people write so many stories about Apple and the iPhone and the iPad and so forth or the iPod where they change the music industry. Most companies can’t do things like that and we’ll have to change that.

Karla Nelson: Love it.

Allen Fahden: So, the Who-Do method then comes from these people and all we do is we put them in the right order. The shaker comes up with ideas, the mover picks the best one and immediately takes it to the prover and says, “Blow whatever hole you can in it.”

Then instead of getting to kill the idea, which they used to do, don’t kill any ideas but that becomes a list of objections and the mover takes that list. Those objections are simply ideas too. Then take those objections back to the shaker.

Karla Nelson: Yeah.

Allen Fahden: We want to keep the shaker and the prover apart because they tend to disagree and that blows up meetings.

Karla Nelson: You got it. That’s the meeting, “Good idea.” “Never going to work.” “Let’s try this.” “No, that sucks.” And you just go back and forth because they’re constantly introducing another idea without even getting all the ideas out on the table before they’re even deciding on which one they’re going to pick, and then figuring out everything that’s wrong with the one that they picked if it passes the sniff test after running the process.

And again, this is the ideation piece that we’re talking about not the implementation. After you run that process as many times as you need to till the prover says, “Okay, I can live with that.”

And for all the listeners, that’s when then you go to the implementation and you pull the maker into the process because you’re going to have to have somebody create those checklists and integrate it into what’s currently there.

Allen Fahden: Yes, and so that will take you through the creating, prioritizing and de-flawing on an idea three to eight times faster than the status quo and it’s even much faster when, in many cases, the status quo is never, it never gets done. Most meetings are like a skit shoot. It’s like pull, bang, pull, bang, you launch an idea and bang it’s shot down.

Karla Nelson: Then everybody is just so tired by the time they pick the most status quo, mediocre, and that’s even if anything ever happens. Or they go, “Oh wow, we picked that one last year and didn’t do anything with it either,” and it just goes under the carpet.

Allen Fahden: That’s right. There is a big, big lump in the carpet. So, let’s take a look at the first Who-Do. The Who-Do method is really not original, it’s just that it is now created to deal with the service economy where 90% of businesses are not making products but they’re delivering services.

They’re doing not tangibles but intangibles. But way back 100 years ago people were making tangible products and it used to be that when you’d manufacture a car, one person would put the car together from beginning to end. They do the whole thing. They’d have a whole bunch of parts laid out in front of them and they’d sit there and they’d assemble the car.

Karla Nelson: For those who’s listening who can’t see the screen, it’s basically Henry Fords, right? He’s the …

Allen Fahden: It’s the before picture of how they used to …

Karla Nelson: When there’s a whole bunch of …

Allen Fahden: Put together an assembler and you had an assistant and they’d be screwing the bolts together on the frame and dropping the engine in themselves. They’d do the whole thing and it took about 12½ hours beginning to end to assemble a car.

So the question is, would these people be able to … Were they good at different parts of it? Did everybody, if you had four or five people assembling their own car, did they go with the same pace on everything? And of course the answer is no. They didn’t, they had different strengths.

Karla Nelson: Yeah. This is where it’s astounding the numbers that you guys are going to see here on this next slide.

Allen Fahden: So basically what they did was they created the assembly line. They standardized the parts and if you were good at axling, you did all the axling. If you were good at engines, you did all the engines. If you were good at the interiors, you did all the interiors and so forth.

So what happened here was the results of this is within six months of Henry Ford’s hiring part plan, the production time went from 12, actually 12½ hours down to what? 1 hour and 26 minutes. That’s about an 8:1 difference. Now, the cost of the car when it took 12½ hours to assemble it was $4,000. At 1 hour, 26 minutes, the price of the car dropped from $4,000 to $600.

Karla Nelson: Wow, incredible. Absolutely incredible.

Allen Fahden: Yeah. So he doubled his workers’ wages because he could afford to do so. They could then afford to buy a car and then when people started driving cars they had to have roads. And once they build roads they needed hotels so people that got far enough away from home they needed a place to stay and they needed restaurants, places to eat. It drove a 17-year surge in the economy. That was the best in history. So that’s what can happen when you get great leverage on your work.

What we’ve done is applied this to companies where one company had done $7 million the year before. They were supposed to double to $15 million and instead we did the Who-Do method and instead of $7 million or $15 million, they hit $29,700,000 in a year.

Another company was doing $20 million. It was the division of a big telecommunications company, within three years they were doing … It went from 20 million to 60 million doing this. So how does it feel to do more with less?

Karla Nelson: Woo-hoo.

Allen Fahden: I think pretty happy because you’re not just making money, you’re making everybody have a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment by doing that.

Karla Nelson: Yes and when 70% of people hate their jobs, this is a way. You’re always going to have to do parts of the work that you don’t like and that you’re not necessarily good at. You can’t do 100% peak work.

Allen Fahden: Right.

Karla Nelson: It’s probably not realistic, maybe in some really interesting scenarios, but it’s not realistic. But guess what? Even if you can move the needle a little, you’re going to be happier, you’re going to move faster and you’re going to have better results.

Allen Fahden: There are 25% of the Fortune 100 are working with us in one stage or another and one of the things that they get out of it, everybody can do, is the difference between week work and peak work. Week work you go home at the end of the day drained. Peak work, you go home at the end of the day happy, engaged.

Karla Nelson: Feeling goody.

Allen Fahden: ”I can’t believe they pay me for doing this.”

Karla Nelson: Yes.

Allen Fahden: Here’s a quick question and we’ll end it. If your day was 50% week work and 50% peak work, would you spend 50% of your time on each showing some equal stacks of paper here. And the answer is no.

Karla Nelson: Oh, and this is incredible, 90:10.

Allen Fahden: 90% week work and 10% peak work, why? Because your peak work you do really fast. You knock it out of the park, you can be so quick on that, but then you get into your weakness and it’s like running through Jell-O. You just can’t seem to make it happen.

So we end with a clock and the clock is a one, two, a three, a three, a three, a three. You ever been in a meeting like that where it’s one o’clock, two o’clock, three o’clock, three o’clock, three o’clock, three o’clock? And you just want to kill yourself to end it or at least get out of the meeting? Well, it doesn’t have to be like that anymore.

Karla Nelson: Woo-hoo.

Allen Fahden: Woo-hoo.

Karla Nelson: We love it.

Allen Fahden: We can instead be people catalysts and put the right people in the right place.

Karla Nelson: All right, it’s not just the people, it’s their chemistry. So thanks so much for joining us.

Allen Fahden: Thank you.

Karla Nelson: I know it as a hectic podcast today and hopefully this helps some of our listeners that wanted really to do a deep dive on the foundation of the Who-Do method. So until next time, we’ll see you soon my friend.

Allen Fahden: Bye, bye.