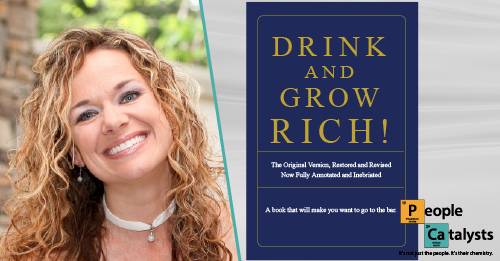

Drink And Grow Rich

We loved Think and Grow Rich from Napoleon Hill, but we changed our title to Drink and Grow Rich, because with 70% of the people hating their jobs, there’s a lot of drinking going on.

So, who writes a book about growing rich during the depression? Someone who wants to grow rich. Everyone noticed this crazy title and the bought the book, Making the author, well, rich.

Listen to the podcast here:

DRINK AND GROW RICH

Karla Nelson: And welcome to the People Catalyst podcast Allen Fahden.

Allen Fahden: Hello Karla.

Karla Nelson: Hello. How are you today, sir?

Allen Fahden: Oh, I’m just having a great time because I’m thinking, and I’m pretty sure I’m going to grow rich.

Karla Nelson: Just by thinking, huh?

Allen Fahden: Just by thinking.

Karla Nelson: No doing necessary.

Allen Fahden: Not a bit of that. No. I’m just thinking. I think I’m going to grow rich.

Karla Nelson: That’s fantastic. Well, Napoleon Hill would be very proud.

Allen Fahden: Yes, he would.

Karla Nelson: For today’s podcast, we’re going to be discussing the world famous book, Think And Grow Rich. It’s actually one of the first business books or it’s actually personal growth meets business books I’ve ever read. It’s by Napoleon Hill. It was published in 1937, during the Great Depression. There’s been over 100 million copies sold and it was inspired by the great Andrew Carnegie, who challenged Napoleon Hill to meet several successful individuals, there was actually quite a few, I’m not even 100% sure how many, and find a common recipe for success. However, for today, the title of our podcast is going to be Drink And Grow Rich.

Allen Fahden: Yes, Drink And Grow Rich, and there’s a purpose for that. I think it’s best explained by a meeting I was lucky enough to have with Larry Wilson, the founder of Wilson Learning, and he looked at me, and it was over lunch and, “Fahden, you know what the definition of pain is?” I said, “No, not really.” He said, “It’s the difference between what we expect and what we get.”

Karla Nelson: Isn’t that so true? Because if you had no expectations, then why would you ever experience the pain, right?

Allen Fahden: Oh yeah. So, I mean, there are a lot of books like this, that basically you don’t have to do anything to get rich. I think what happens, why would you drink, well you drink because you want to soothe that pain. I remember speaking for a group called Disrupt HR, and it showed a sign that said, “There’s a place for all you disengaged employees, and it’s called the bar. That’s where we meet every night.”

Karla Nelson: I love that one. That was a good find, for sure. In Think And Grow Rich, it talks about 13 principles. Now, of course, all of these principles, and Allen you actually hit the nail on the head as far as there’s so many business and self improvement books that they tell you the problem over and over again, and you agree with the principles, and on this podcast, we talk about, “Well then, how do you take that and get to implementation?” So, within Think And Grow Rich, there’s 13 principles which are desire, faith, autosuggestion, specialized knowledge, and it’s actually general knowledge as well, they juxtaposed those, imagination, organized planning, decision, persistence, power of the mastermind, sex transmutation, and you can look that one up on Google, subconscious mind, the brain, and the sixth sense.

So, we’re not going to talk about all those today but we’ll pull out a couple here in just a moment. I also wanted to highlight two quotes that have really become world famous quotes, that Napoleon Hill had in his book, which is, “A goal is a dream with a deadline,” and one of the other quotes is, “Whatever the mind of man can conceive and believe, it can achieve.” I actually forgot about that one. I remember reading the book long ago. Gosh, maybe 20 years ago. I can’t believe it’s been that long. It doesn’t seem like that long.

But re-reading and going through it, just all of these principles we’re going to say yes to. Like many other business and self-improvement books, it’s not that what they’re stating is not accurate, it’s just that where’s that dissonance between saying, “Yes, that’s the way” and two, doing it, right? So what’s the idea as we call ideation implementation? But the book was extremely successful. One of the things I think is interesting, Allen, is who writes a book called Think And Grow Rich during the Great Depression? I mean, it’s just so, “Really?”

Allen Fahden: Yeah, exactly. It was like, “What?” But if you want to be successful, there’s a lot of evidence that says, “Hey, look at what everybody else is doing and do the opposite.” There’s-

Karla Nelson: We actually have a word for that with the People Catalyst. It’s called oppotunity.

Allen Fahden: Oppotunity: An opportunity that is caused by a unity of opposites. Oppotunity, and how do you find that? Well, let’s talk about some possibilities, as far as the stories when it actually happened. I think one of the great conclusions about that, one of the things that Niels Bohr, who’s a Danish physicist, who won the Nobel Prize in 1923 for physics, and he said that the opposite of any truth is not necessarily a falsehood. It’s often an even greater truth.

So, don’t be afraid to look at the opposite of what is true today because so much change is cyclical, and that means it’s going to change to the opposite. Hairstyles get longer, they get shorter, they get longer. Ties get longer, they get shorter, they get longer.

Karla Nelson: Pants get looser, get tighter, get looser.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, that’s right.

Karla Nelson: Waistline, or as like as high up on the waist, it’s hilarious. Now that I’m old enough to see, I can’t even believe some of the fashion that actually does come back around.

Allen Fahden: Oh yes. Indeed. Of course, sometimes you have to wait until people are so young that they don’t remember the last time it was in, so-

Karla Nelson: Ah. I remember–

Allen Fahden: … they think it’s their own, it’s new.

Karla Nelson: … like, “You think that’s new?” Well, I love Niels Bohr’s work, and one of the other quotes that he is well known for is, “Until we discover the paradox, we have not yet begun to solve the problem.” I think people try to solve the problem too quickly.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely. When you discover the paradox, it’s often emotionally an even more powerful solution. For example, why would you write a book during the Great Depression, and especially why would you put the title that you can get rich? Kind of crazy.

Karla Nelson: That’s just funny when you actually think about it. When I said it, it was one thing. You just said it again, and it just made me chuckle.

Allen Fahden: Yes. One way to look for justification is, there’s a great book by Renee Mauborgne and Chan Kim called Blue Ocean Strategy. They talk about uncontested marketspace, you know? If you do the opposite of what everyone’s doing, in a time when you shouldn’t even be doing it, well then you’re not going to have any competition. They call that the blue ocean, there are no fish, sharks around waiting to attack you. It’s uncontested marketspace, and the data says that basically you can double your revenue, and you can quadruple your products, simply by doing what you normally do, except for occupying uncontested marketspace.

Karla Nelson: I love it. In addition, I think the title of the book, too, is that big, huge problem, right? To solve. So, it’s almost like, it’s similar to the changing of the world, right? I think it gave a lot of people a shred of hope during a really challenging time and, “Really? Can this happen?” Solving this big problem, and the truth of the matter is, and I believe this was gosh, I can’t remember who came out with this stat. I know Bloomberg is the one who reported it in an article, is that you’re 80% more likely to become a millionaire during the downtime than the good times. It’s really the opposite of what most people think.

Allen Fahden: Yeah. Absolutely. But then when you think about it, that’s a paradox, and of course, you see that during the Great Depression, Chevy actually passed Ford up as the number on brand of model of car, and Kellogg’s-

Karla Nelson: Which is saying something, because the car had only been around for how long? Geeze.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, 20 years or so. But Ford pulled in their horns and Chevy went for it. They went totally aggressive during that period of time. Same was true for Kellogg’s cereals who passed up Post cereals as the number one cereal during that time. If you think that’s crazy, how about this? During 1930, the first year of the depression, right after the stock market crashed where everybody lost all their money, Henry Luce publishes a magazine–

Karla Nelson: I love this.

Allen Fahden: … called Fortune. Really?

Karla Nelson: You just lost off your money. Why not come out with a magazine called Fortune?

Allen Fahden: Yeah, sure. Why not? It was immediately successful in terms of subscribers, and I think you told me that they charged a dollar for it, which was like $15 today.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, can you imagine? Paying $15 for a magazine today, it’s unheard of, right?

Allen Fahden: Right.

Karla Nelson: Let alone after the market crashed in 1929 and launched it in 1930, yeah. It’s so interesting. So many times it’s the opposite of what we believe, too. And we’re afraid of it. Those that actually stepped into it, I think he later, I mean he’s the creator of Time and-

Allen Fahden: Sports Illustrated.

Karla Nelson: … Sports Illustrated, and pretty much every huge, at least four or five huge publications that are still in circulation today, but that was the first one he came out with, yeah. It’s amazing. Let’s talk about the next, or the breaking down a couple of these principles. Like I said, we can’t go through all 13 of them, but we can talk about 6 of 13, and what we want to do is give you some information to be able to turn the principle into action and implementation, and also understand why a lot of times it’s like, “Hey, this is what you need to do” but it’s not your core nature to be able to do that, let alone do it well.

So, we’re going to talk about six of these principles and then also give you some input on how you can utilize the principle, understand it, and then get to the point of doing something with it. The first we’re going to talk about is desire, right?

Allen Fahden: Yes.

Karla Nelson: People, and I think this is most people, they have the desire. They’re fired up, and they want to implement, but they end up burnt out. They’re trying to do too much, they’re trying to do things that they’re not good at, and in the end, they become disappointed, and I would even say that many get completely cynical, right? Because they have the desire, they’re fired up, they want to go, so desire in of itself is often times just not enough.

Allen Fahden: Yes. And cynical, and it’s probably evidence going back to, “There’s a place for this, it’s called the bar, and we meet there every night.” That’s cynical.

Karla Nelson: There’s a reason why that sign and there’s so much truth to that, right? Is because it’s that disappointment. The longer you go with a desire that you’re not achieving, I mean, it’s just this cyclical, “I’m fired up, I’m burnt out, I’m fired up, I’m burnt out” and then you’re just like, “I’m just wiping my hands of this.”

Allen Fahden: Absolutely. Two ways the flame can go. Our friend, Marshall Thurber, probably showed the positive side of desire, because you’ve got to have the desire. Simon Sinek talks about that, too. You’ve got to have your why, and on its own, the desire can do a lot. I want to share a little about that, Marshall was called up to a community in Alaska where the high school seniors have a 12% suicide rate.

They asked him to encourage, do something that motivated these kids to learn so that they would not be, their lives wouldn’t be so hopeless. He was given eight days, and at the end of the fifth day, they were getting impatient with him because he wasn’t teaching them anything. He was supposed to be, they were teachers, so they thought he should be teaching them content. No, that’s not why he was there. He thought he should be giving them the desire to learn. He spent five days on the desire to learn, through questioning, interaction. They’re getting all impatient, and they actually found out that the last couple of days, he did get into the content, but not until they had the desire to learn.

The desire alone is a great first step, and it’s also not enough. If he had have left at the end of the fifth day and just given them the desire to learn.

Karla Nelson: They would have been frustrated, like, “What?”

Allen Fahden: They would have been at the bar, too.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, there’s the disappointment. There’s that cliff, right? That happens. “I’ve got desire, I read this great book, I’m so fired up.” Womp womp womp, right?

Allen Fahden: Yes. Your hopes are-

Karla Nelson: How often does that happen?

Allen Fahden: … dashed again, mwahahaha.

Karla Nelson: Exactly. And depending on the information that you have, it’s like even it kind of reminds me of going to … I know you always call it seminar breath. You go, you’re excited, and you’re there, and you’re present. What they’re saying, it’s not that it’s not truth, it’s just that you’re you, right? You have your core nature, and you need all four. We look at ourselves to manage it all, or we miscast our team. All of that, the desire, it actually can fuel leaving dead bodies behind you, too, and a whole bunch of other frustrating things where it’s not only you that’s disappointed, you’re actually creating disappointment for everyone around you. Hence the reason why 70% of people hate their jobs, right?

Allen Fahden: Yeah, there’s nothing worse than somebody who’s highly motivated and does the wrong thing. Because it makes it worse.

Karla Nelson: It is. And you overlay the core nature of work, and it’s like you’ve got to have lead, desire, shaker, they’re going to come up with a new idea every other day and drive people crazy, right? Understanding that is really important, so desire is great, but desire alone can create complete burnout. So, let’s move to the next one, because we could talk about that for an entire podcast. The next principle we’re going to talk about is knowledge, and in the book, Think And Grow Rich, it talks about general knowledge and specialized knowledge. This actually reminds me of Henry Ford, Allen, because they kind of lean in the book that specialized is much better, but you have to have both, and that you make more money, which I would have to say in some situations, that’s correct.

But look what Henry Ford did. He was a complete generalist and he hired people around him like his CFO, right? To save himself from himself. Because the first two ventures he did completely miserably failed, and the last investor that was going to invest in the Model T and Ford Motor Company said, “Ugh, ugh, ugh. I will not invest in you unless you take on these individuals to save yourself from yourself.”

Allen Fahden: Yep, that’s right. And so as they went on, and they were successful, one of the things that Henry Ford didn’t want to do was reward his employees who built the car as part of their success. The CFO, who he was advised by the investors to hire said, “Hey, look, we’ve got to raise the wages of these people” and Ford didn’t want to do this. This story comes out of Ernesto Sirolli’s wonderful book, and so finally, Ford relented and he doubled his workers’ wages, and more good things happened to him. All of a sudden, they could afford to actually buy the car that they were building, which then there were so many people buying cars, because they could afford them, that they had to build roads.

And then when they built roads, then they had to build restaurants and hotels on roads, and it drove a booming economy, like until 1929. It was about 15 years of a booming economy, just from that.

Karla Nelson: Yeah, that’s pretty cool. Think about it, though. Literally built the company, and he would have never done it, right? But again, that’s the … He had specialized numbered knowledge, right? Where Henry Ford was a generalist. It literally raised the competent. Launched the company.

Allen Fahden: We’ve put that into perspective for you, which is where you think, because there’s been an argument for decades about whether you should specialize or generalize and what we say is specialize in your role. What is your role? Your role is based on what your core nature is, and so for example, I’m a shaker. Well, get me coming up with ideas, because I’m going to hit it out of the park, and I’m going to do it fast, and I’m going to keep doing it, as long as is needed, but don’t get me doing expense reports, because I’m going to mess it all up and I’ll be bored to death.

So, specialize in your role and then generalize in what you know, because one of the things that happens is that when people are getting together and thinking and deciding what to do, if you can bring information in from outside the context of what you’re doing, that’s generalized knowledge, then you bring a different perspective in, and you bring in often times the “Uh-huh” that makes you have a much better idea of what to do, a much better strategy, and much better thinking.

Karla Nelson: Yes, I agree. Let everybody share their role in core nature, and then also bring in that … We’ve seen that many times over again, because you get lost in yourself, too. It’s just not about your knowledge, but allowing other knowledge to come in. We could talk about that forever, too. Okay, next principle, and I love this one, imagination, right? Oh, gosh. Tell that to a maker, they would just die, but there’s really two types of imagination that they talk about, which is synthetic, which is looking back.

So basically your imagination comes from what’s happened previously in the past, and then creative imagination which is looking forward or what are the possibilities, right?

Allen Fahden: That’s right.

Karla Nelson: Kind of interesting to think about what your core nature is and how you’d look at that.

Allen Fahden: Well yeah. And think about this. There’s a perfect correlation there, because the mover and the shaker are the early adopters. What do the early adopters do? They look ahead. They’re the ones who use the creative imagination, so they’re into possibility. Whereas the late adopters, the provers and makers, are much more into looking back–

Karla Nelson: What went wrong last time?

Allen Fahden: … and reality, yeah.

Karla Nelson: That’s never going to work because we already tried it.

Allen Fahden: We tried that, and oh, don’t bring that in here, it’s going to disrupt the whole system. They’re looking to warn you about what can go wrong, and it’s perfect because they are looking backward at reality. The early adopters are looking forward at possibilities. That’s why you not only have these two kinds of information, but think about the who, and the when. The who is that it’s the later adopters, the provers and shakers, who should be doing the synthetic, looking back, and it’s the movers and … Excuse me. Movers and shakers who should be doing the creative, the looking ahead.

Karla Nelson: Love that, love that. We’ll move on, since we’re trying to shove a ton, like a day’s worth of conversation into a half hour podcast. Okay, the next principle we’re going to talk about, and I really like this one because I think people beat themselves up on both sides of the coin on this, and if they just had all core natures of work showing up, it would help everyone. The decision versus procrastination, okay? This to me is you’re in it, like many of these principles and the ones that we picked out primarily, you’re asking somebody to be something that they’re not.

So, when you think of decision, and you think of the who do model that we utilize, we have doing decision, versus thinking, which is seen as procrastination. However, your doers and your thinkers are different people, completely. So, how are you just saying, “Okay, you need to be a doer?” Because that’s really what the book said. Don’t procrastinate, take action. But you’ve got to take the right action, and you need to take an action that has your doers and your thinkers, not just your doers, or else you’re going to blow the budget, go overboard, and potentially crash the company, if you’re just doing without thinking. I mean, heck, you should think 80% of the time and do 20%.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, absolutely. Most people have that backwards.

Karla Nelson: We’ve seen that in our classes quite a few times.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, everybody wants to jump in and start doing stuff, and they haven’t even thought about what they’re doing yet.

Karla Nelson: Even after we teach the model, that’s the crazy part about it. You’re like teaching them, and then you give them a task and they go right back to-

Allen Fahden: That’s right.

Karla Nelson: Because we can’t change who we are.

Allen Fahden: They got all excited.

Karla Nelson: Yep, exactly. Got to get doing, got to get doing, got to get doing.

Allen Fahden: That’s right, the brain shuts down and here we go. The WHO-Do method actually allows people to make decisions based on the contribution of each core nature, and the process forces you to have the discipline of doing enough thinking, of doing that 80% thinking, not getting too excited about going ahead, but at the same time not leaving a meeting saying, “Nothing’s ever going to happen.” Because it allows people to, as individuals, to respect their own individuality as a member of the team. They don’t have to sacrifice themselves, because each core nature is called upon to contribute to the decision at just the right time. Everybody gets to put their imprint on it in a positive way and not be judged.

Karla Nelson: Like we always say, we need you all, but we just need you at different times. There’s different times during the process with ideation and implementation that you balance back and forth. I love that. Everybody gets to put their imprint on it, because we need everybody. We’ll talk a little bit in a moment about being marginalized and what that creates, if you don’t identify everybody for their unique role and core nature. Okay, so the next one we’re going to move onto is the mastermind. I love this one, because I think it’s like the biggest over-generalized term that could probably happen in business books and personal growth.

Which is fantastic, by the way, the mastermind’s amazing, right? We all say yes to it and we know that it’s a great thing to be with other individuals. I think the identifying thing is that you have to define the context of the mastermind, which doesn’t happen frequently. It’s one thing to be around “like-minded people” but it’s a completely nother thing to be around who is in this mastermind, right? Is it a book club? That’s a type of mastermind, because you’re getting different perspectives on a book. That’s typically a type of mastermind. Often times they call it a mastermind, and they’re just sending referrals back and forth.

So, really you can utilize the who-do method to create the context so that what happens is that everyone showing up is showing up for the same reason. Otherwise, you see this, and Allen that’s probably why I don’t belong to many masterminds, not that I don’t, it’s just that a lot of them, if the context isn’t created appropriately, you’ve just got this ping ponging thing going on the entire time.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, absolutely. I’ve been in some good ones and some really, really bad ones. I think one of the things that you mentioned is getting everybody understanding and agreeing to what a mastermind is for, and what that particular mastermind is for, around the purpose.

Karla Nelson: And also identifying like what each core nature, they respond differently completely. And it’s a mess if the leader doesn’t understand the who-do method, if it’s about getting something done. Or even people getting their feelings hurt, or whatever.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely. Everybody talks about Carnegie and Alexander Graham Bell, Thomas Edison, they all had mastermind groups and they met in Florida, and they were very successful, but it’s a very different thing what happens when people join a mastermind group. Often times the, for example, shakers and provers who are the thinkers, like to test ideas but often times the agenda is not to listen to what people, how they react to the idea as much as it is to try to get people to praise them for how great their ideas are. You can tell how dysfunctional that meeting gets.

How makers, on the other hand, are pretty much sitting there and maybe in a lot of ways don’t want to be there, and are just hoping somebody gives them a referral or something like that.

Karla Nelson: They typically have a different agenda, for sure, and even if it’s listening, okay that’s listening, but again, what’s the context here? The context of the meeting determines so much and often times it’s just not identified. For a maker, I think that would be extremely, the most challenging for them.

Allen Fahden: Yeah, oh absolutely. Because usually in meetings they don’t want to be there anyways, as we’ve said so many times. So, gosh, we’ve seen all of these people, and so one thing is to get everybody’s purpose clear, but also to identify people and contextualize their responses by what their core nature is. If I ask, test an idea on a shaker, that shaker’s going to say, “Well, that’s a pretty nice idea, but I’ve got six more. How about this? How about this? How about this? Why don’t you do mine?”

Whereas a maker might just want more and more and more detail, and more and more detail, and maybe shaker’s testing that idea, and the maker is just sitting there saying, “Well, you’re not giving me the detail” and the shaker’s saying, “Well, I haven’t thought of it yet.” So you can really get into it. It can be a mess and people can go away unhappy, and even a blind squirrel will get an acorn once in a while. Sometimes you get something out of it.

Karla Nelson: And the other piece, that’s why they fall apart and don’t stay together long term, because they haven’t set that and understood that. You miss a lot of the opportunity of the power of the mastermind when you don’t utilize that. Okay, so let’s go ahead and move on to our last principle which this is a really good one, which understanding it, and we’re not going to talk about it in a personal fashion, but in a business fashion, which is fear, right?

Fear is actually when we overlay the who-do method, and each core nature, we experience fear very differently. So, a shaker experiences it because, “Oh, my gosh, they’re going to think my idea’s not good. They don’t like my idea, they don’t like me.” They’re going to think, “Oh, squirrel, my head’s in the clouds,” right? And so they have to identify that that is your fear, and then a mover, their typical fear is there’s two of them. The first is they’re going to see me as pushy, or always having to be in control.

And the second fear is that you’re going to go into a meeting, you don’t have the ability to facilitate or have somebody else. You don’t care if somebody else facilitates, you just want an ends to a mean, or a means to an end. You want something to happen. Movers become completely disengaged if that’s not … In any meeting. Let alone, I mean a mastermind meeting, a business meeting, phone call. Doesn’t even matter.

If that’s not happening, our fear is we’re going to waste an hour of our life and we could be doing something different. The prover, their fear is, “Oh, my gosh, if I point something out, I’m going to be seen as negative. Negative Nelly.” Or, “Gosh, she’s such a Debbie Downer. Such a pessimist.” And so then the maker’s fear is, “They’re going to actually make me contribute and say something, and I have a ton of stuff to do back at my desk and I’ve got some checklists to eat.”

So, we have to be aware of what our fear is associated with our core nature of work when we’re working with a team. And again, fear we could talk about for a day in of itself, but we’re overlaying this with the who-do method in overcoming those fears that can be created by your role.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely. It really comes down to the fear of being fired or sometimes even-worse, emotionally, being marginalized. “Sit in your office and shut up” and then people talk about you in the hall, that you’re an idiot or whatever. That’s-

Karla Nelson: I’ve never heard of that happening.

Allen Fahden: No, no, no. That’s not too pleasant. The fear of being fired is an interesting one, and I remember we worked with one of the regional Bell operating companies and it was about the time of downsizing, and they decided to-

Karla Nelson: Oh, I know who you’re talking about. This is a great story.

Allen Fahden: They decided to get rid of, and they didn’t even know who the makers were, but they perceived the makers in their negativity, of course, which is they’re detail people, and of course, they resist change.

Karla Nelson: Didn’t they set the agenda, they just wanted to be innovative?

Allen Fahden: Yeah, “We’re going to be innovative, so we’re going to get rid of everybody who’s afraid of change.” So they did that, and they fired all these makers and I remember this, here’s what happened immediately. That to get a new telephone, the time used to be … I’m sorry. Used to be a half a day, the response time. Then, within I guess about two or three days, the response time went down from a half a day to something like 30 days-

Karla Nelson: It was almost 30 days.

Allen Fahden: … phone, and I remember getting back from an out of the country trip and my voicemail had been shunted over to some concrete company. Somebody else entirely.

Karla Nelson: Somebody had your phone number.

Allen Fahden: Because they didn’t have any people who could do the details well, and if you think about it, when you understand people’s core nature, now you have an opportunity to hold them in their excellence instead of their smallness.

Karla Nelson: You literally just took the words out of my mouth. You can remove their fear and allow them to step into their brilliance by removing the fear of saying, “I appreciate you for what you are” and not expecting them to be something different. Or, like you said, marginalize them. A lot of times movers and shakers, and it is even cliché, that they are valued more than provers and makers. But we need everyone equally. We just need you at different times.

Allen Fahden: At different times.

Karla Nelson: So with that said, thanks so much for joining me today, Allen. I’m loving this series. I love going back to these books that, many of them are some of the first business books that I read, and I can feel, I kind of get elated because I remember the frustration and the burnout and the disappointment that I had. So, our why, our big why is to revolutionize the way work is done.

Allen Fahden: Absolutely.

Karla Nelson: I’m so excited we found this process. It makes life amazing, and being able to bless others with it as well. If you’d like to hear more information or learn more about the People Catalyst, visit us at ThePeopleCatalyst.com. Thanks again Allen.

Allen Fahden: Thank you.